White Paper: Layoffs as Organizational Transitions

What the Evidence Shows About Uncertainty, Leadership Strain, and the Long Tail of Change

Abstract

Layoffs are commonly treated as discrete operational interventions aimed at correcting financial or strategic misalignment. However, qualitative evidence from leadership interviews and employee surveys, when examined alongside established organizational research, suggests that layoffs function more accurately as extended organizational transitions with durable psychological, cultural, and performance-related consequences. This article synthesizes qualitative signal with peer-reviewed research to examine three consistently underestimated dynamics: uncertainty, survivor effects, and leadership strain. Together, the evidence indicates that many organizations incur avoidable downstream costs not because of flawed decisions, but because they fail to design for the human arc of the transition.

Methodology & Evidence Base

This analysis integrates three sources of insight:

Qualitative employee and leader surveys examining experiences of navigating, executing, or surviving layoffs,

Structured leadership interviews with senior leaders and people managers,

Peer-reviewed research from organizational psychology, management, and restructuring literature.

Survey and interview data are treated as qualitative signal, not statistical inference. Their role is interpretive, helping explain why empirically observed outcomes occur. Where qualitative observations converge with established research findings, confidence in conclusions is high.

Layoffs Are Not Events — They Are Transitions

Most organizations implicitly treat layoffs as events: a decision is made, an announcement is delivered, exits are executed, and the organization moves on.

However, transition theory and restructuring research indicate that layoffs are better understood as prolonged psychological and relational processes. While operational change may be completed quickly, human adaptation lags - often by months. Crucially, most measurable harm associated with layoffs emerges after the formal reduction is complete.

This mismatch between operational closure and human recovery is not philosophical. It is observable in performance data.

The Afterlife of Layoffs Is Measurable

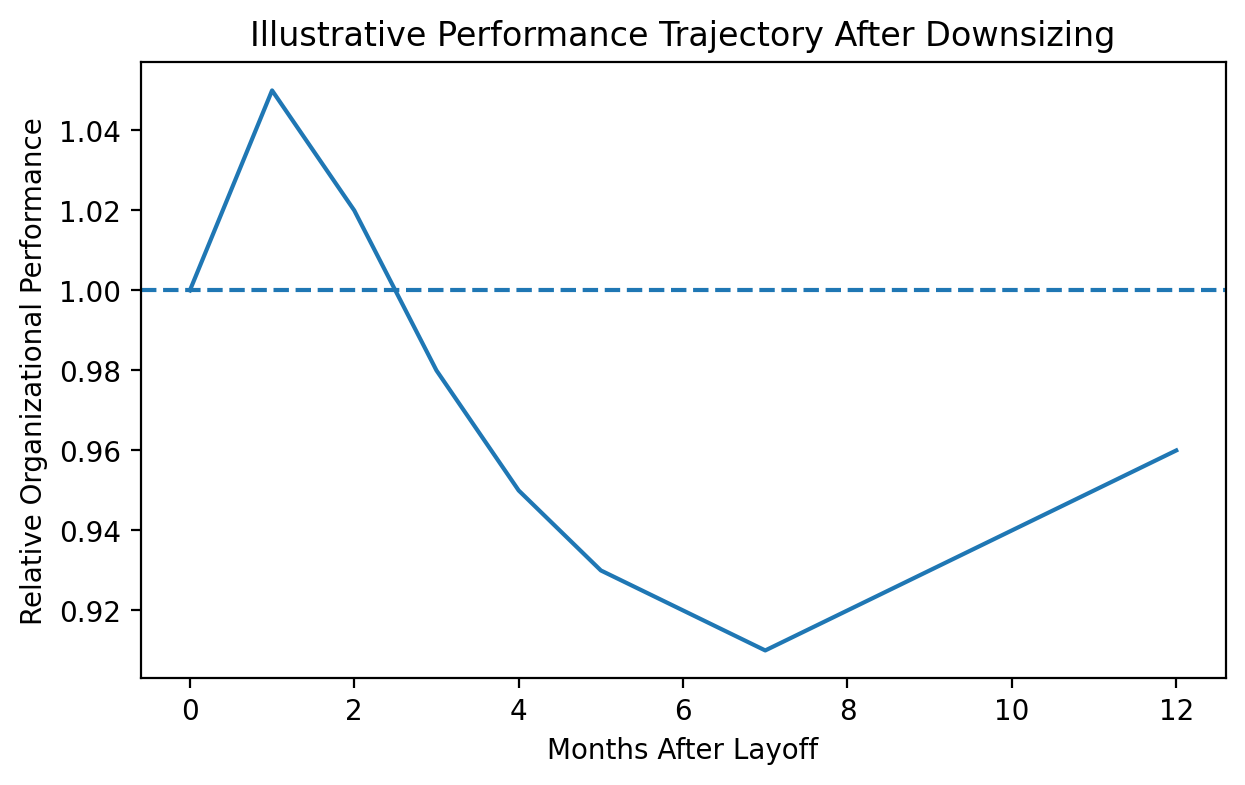

Figure 1. Post-Layoff Organizational Performance Over Time

Illustrative redraw based on Datta et al. (2010). This figure represents the commonly observed pattern across downsizing studies: immediate cost relief followed by declines in productivity, quality, and innovation lasting 6–12 months or longer.

Longitudinal research on downsizing consistently shows that while layoffs produce rapid financial savings, they are frequently followed by medium-term declines in organizational performance. These declines persist even when adjusted for reduced headcount, indicating that the effects are not explained by capacity alone (Datta et al., 2010; Cascio, 2002).

Interpretation:

Layoffs often succeed financially while simultaneously degrading the conditions required for sustained performance. The “afterlife” of a layoff is not anecdotal - it is empirically observable.

Uncertainty Is More Damaging Than Bad News

Across leadership interviews and survey responses, uncertainty emerged as the most frequently cited source of distress. This aligns closely with decades of research on job insecurity and organizational change.

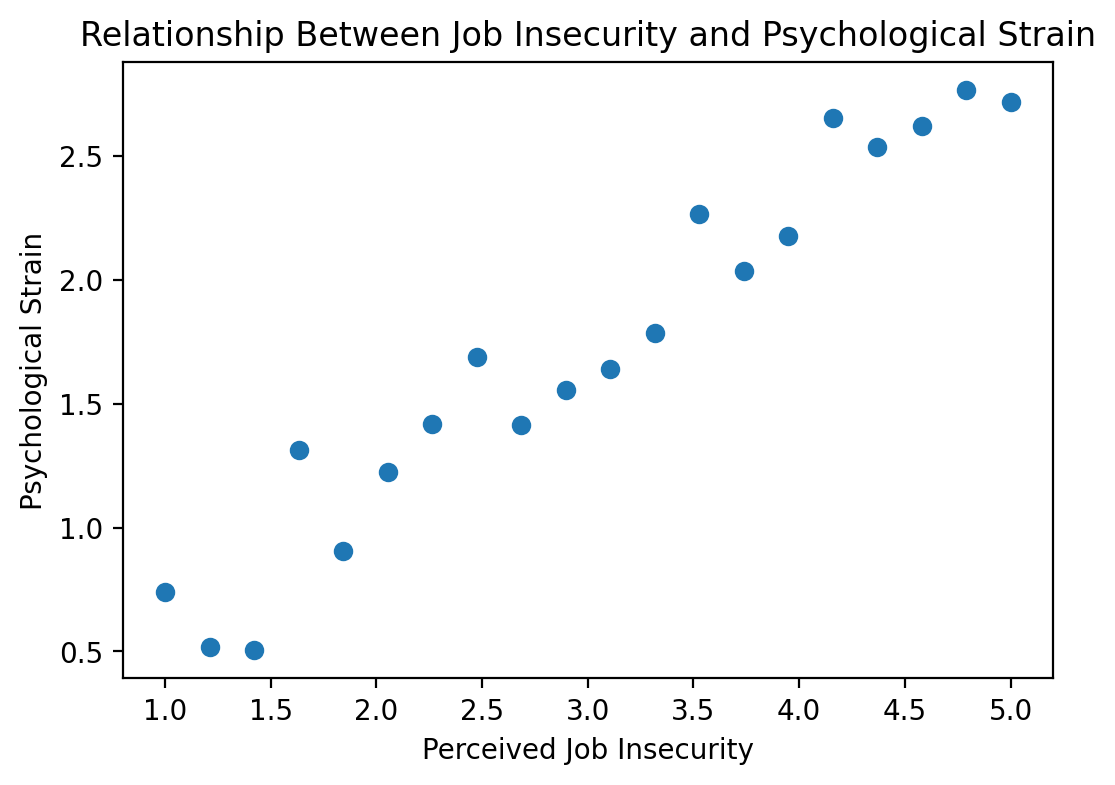

Figure 2. Relationship Between Job Insecurity and Psychological Strain

Illustrative redraw based on Ashford, Lee, & Bobko (1989). Higher perceived job insecurity is associated with increased psychological strain, independent of actual job loss.

Research demonstrates that perceived job insecurity alone - even in the absence of layoffs - predicts anxiety, withdrawal behaviors, reduced performance, and erosion of trust (Ashford et al., 1989; Bordia et al., 2004). Silence intended to protect employees often increases cognitive load by forcing individuals to fill informational gaps themselves.

Interpretation:

From a systems perspective, uncertainty is not neutral. It actively degrades decision-making and focus, making early framing a risk-reduction strategy rather than a cultural preference.

Survivors Are a Risk Population, Not a Success Case

One of the most robust findings in downsizing research is that layoffs affect far more people than those who leave. Employees who remain often experience what researchers term “survivor syndrome.”

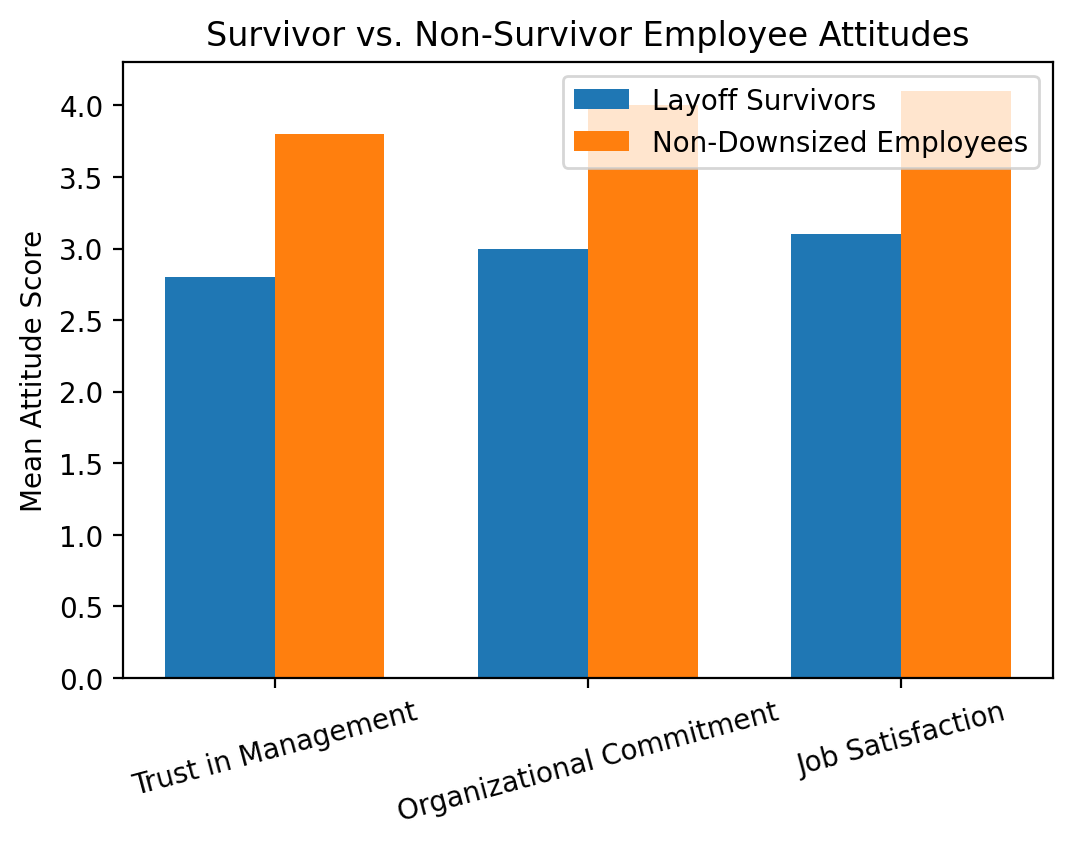

Figure 3. Survivor vs. Non-Survivor Employee Attitudes

Illustrative redraw based on Brockner et al. (1992). Employees who remain after layoffs report significantly lower trust in management, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction compared to employees in non-downsized organizations.

Survivors frequently report guilt, anxiety, diminished trust in leadership, and reduced commitment - effects that persist long after headcount stabilizes (Brockner et al., 1992).

Interpretation:

Layoffs are not contained events. They restructure the psychological contract for those who remain, with predictable consequences for engagement, retention, and discretionary effort.

How Layoffs Are Handled Matters as Much as Who Is Cut

A common leadership assumption is that negative outcomes are inevitable once layoffs occur. However, research on procedural justice complicates this narrative.

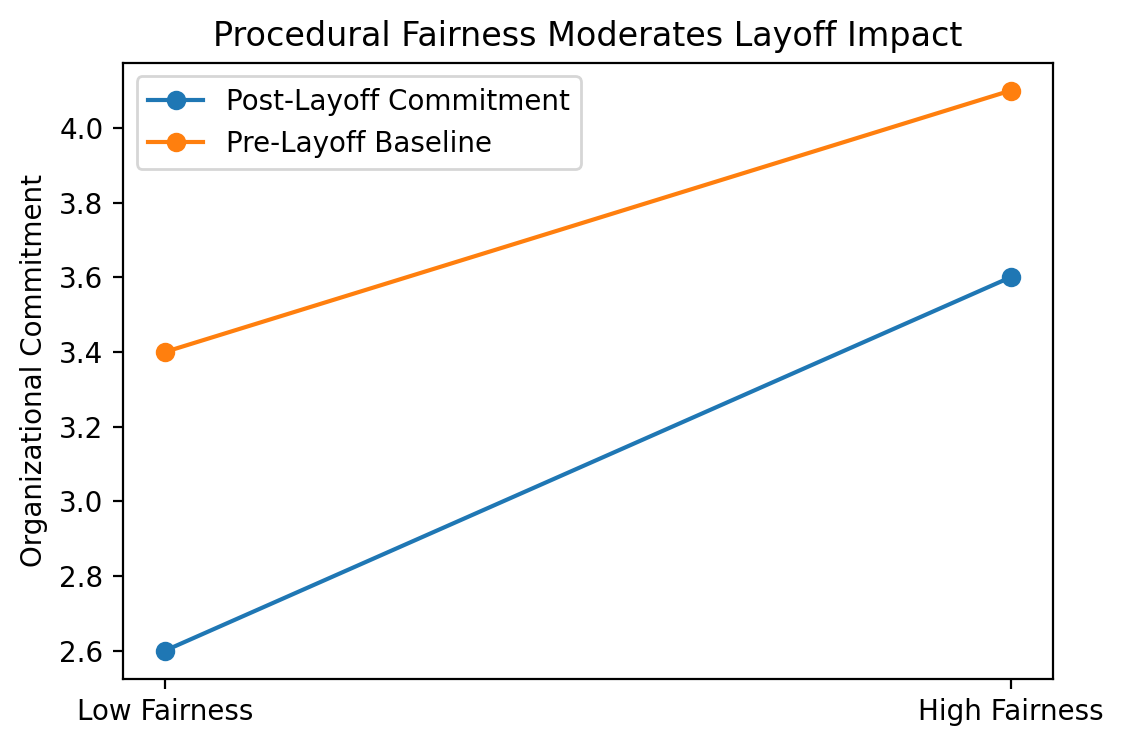

Figure 4. Procedural Fairness Buffers Negative Layoff Effects

Illustrative redraw based on Brockner et al., (1995). Research shows that when layoffs are perceived as procedurally fair, meaning the process is transparent, consistent, and explained clearly, negative reactions among both laid-off employees and survivors are significantly mitigated.

Employees’ perceptions of how decisions are made and communicated strongly moderate post-layoff outcomes. Even when outcomes are unfavorable, transparent and respectful processes preserve higher levels of trust and cooperation (Brockner et al., 1995).

Interpretation:

Speed versus humanity is a false tradeoff. The evidence suggests the real risk lies in prolonged ambiguity or abrupt, opaque execution—both of which amplify downstream harm.

Leadership and Managerial Strain Is Systematically Underestimated

Leadership interviews consistently surfaced the psychological burden of foreknowledge and emotional containment. Research supports this pattern, particularly for middle managers, who experience higher burnout and turnover risk following layoffs (Kets de Vries & Balazs, 1997).

Managers are expected to deliver decisions they did not design, regulate team emotions, and rapidly restore productivity often without sustained support once notifications are complete.

Interpretation:

When organizations fail to support managers through and after layoffs, they risk losing precisely the leadership capacity required for recovery.

Conclusion: Designing for the Human Arc

Taken together, the evidence points to a consistent conclusion:

Layoffs fail less often because of flawed strategic decisions and more often because organizations design for operational closure rather than human transition.

Uncertainty has a measurable cost.

Survivor effects are predictable.

Leadership strain is real and consequential.

Organizations that plan explicitly for the human arc - before, during, and after layoffs - recover faster and preserve trust, performance, and leadership capacity. Those that do not often experience prolonged erosion disguised as stabilization.

Clarity functions as care.

Silence is not neutral.

And leadership, in these moments, is a matter of design.

References (Selected)

Ashford, S. J., Lee, C., & Bobko, P. (1989). Academy of Management Journal, 32(4), 803–829.

Bordia, P. et al. (2004). Journal of Business and Psychology, 18(4), 507–532.

Brockner, J. et al. (1992). Administrative Science Quarterly, 37(4), 526–541.

Brockner, J., Wiesenfeld, B. M., & Martin, C. L. (1995). Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 63(1), 59–68.

Cascio, W. F. (2002). Academy of Management Executive, 16(3), 80–95.

Datta, D. K. et al. (2010). Journal of Management, 36(1), 281–348.

Kets de Vries, M. F. R., & Balazs, K. (1997). Human Relations, 50(1), 11–50.

Methodological Note: Use of Illustrative Figures

The figures included in this article are ethically redrawn, illustrative representations of relationships documented in peer-reviewed research. They are not reproductions of original charts, nor do they imply access to proprietary datasets or raw study data.

Each figure is based on patterns consistently reported across the cited studies, including directionality, relative magnitude, and temporal effects. The purpose of these redraws is interpretive rather than replicative: to make empirically established relationships legible to a broader leadership audience while preserving fidelity to the underlying research.

This approach is standard in academic synthesis and applied scholarship, particularly when:

Original figures are embedded in paywalled journals,

Multiple studies converge on the same directional findings,

The goal is conceptual clarity rather than statistical replication.

Where figures reflect synthesized patterns (e.g., post-layoff performance trajectories), this is explicitly noted in captions. Readers seeking original statistical models, effect sizes, or methodological detail are encouraged to consult the primary sources listed in the references.

Qualitative survey responses and leadership interviews referenced in this article were treated as thematic signal, not as statistically generalizable evidence. Their role is to contextualize and interpret empirical findings, not to substitute for them.

This combination of qualitative insight and established research reflects a research-translation methodology: grounding leadership practice in evidence while acknowledging the lived complexity of organizational change.